Parties better off pursuing vote reform than non-compete agreements

November 27, 2013 3 Comments

It’s an idea that has come up repeatedly in Canadian history: the idea that two or more Canadian political parties should rally behind only one candidate to prevent a mutual enemy from winning an election.

It was tried with little success in the 1973 Manitoba provincial election, when Winnipeg Free Press publisher R. S. Malone and lawyer William Palk organized the Group for Good Government, an effort to convince the Progressive Conservatives and Liberals to enter into non-compete agreements so that Ed Schreyer’s left-of-centre NDP government could be more easily defeated.

Only nine of 57 constituencies saw reduced competition, and Schreyer’s government was easily re-elected.

The idea came up again in 1988, when it was suggested in some circles that the federal Liberals and NDP join forces to ensure that Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government — and with it, the controversial Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement — be defeated. Neither happened.

More recently, an NDP activist in Brandon-Souris, a normally reliably Conservative constituency in Manitoba’s southwestern corner, suggested that the Liberals, NDP and Greens put aside their differences and unite behind a single candidate to defeat Conservative candidate Larry Maguire.

Monday’s by-election, prompted by former Conservative MP Merv Tweed’s departure from politics to the business world, must have felt like a told-you-so moment for proponents of a single non-Conservative candidate, as the absence of a Green or NDP candidate could have changed the outcome:

Larry Maguire (Conservative) — 12,205 votes

Rolf Dinsdale (Liberal) — 11,816 votes

Cory Szczepanski (NDP) — 1,996 votes

David Neufeld (Green) — 1,349 votes

Frank Godon (Libertarian) — 271 votes

(Results as posted on the Elections Canada web site as of 7:48 p.m. Central time, Nov. 27)

Yet, there is little sense in parties yielding the field to help defeat a mutual rival, even if there is little hope of winning. Not only do relatively hopeless elections offer parties a chance to engage card-carrying party members in something more vigorous than waiting for the next newsletter to arrive in the mail, they also allow for the sale of new memberships.

Such races also allow rookie candidates destined for greater things to gain valuable political experience. Future 1981-88 NDP premier Howard Pawley got his start in politics as an otherwise forgettable third-place candidate in The Pas in the 1958 provincial election. Vic Toews, a future Attorney-General of Canada, started off with the unprestigious job of running as the Progressive Conservative candidate in the provincial Elmwood constituency in 1990, winning enough votes for a second-place finish. Lloyd Axworthy, Canada’s future foreign minister, only succeeded in getting elected on his third try, as a provincial Liberal candidate in Fort Rouge in 1973, having been previously defeated as a provincial candidate in St. James in 1966 and as a federal parliamentary candidate in Winnipeg North Centre in 1968.

Thus there are benefits to be gained even in losing — benefits that would disappear if long-shot parties vacate the field entirely.

The idea of political parties entering into non-compete agreements also carry the questionable assumption that those who would ordinarily vote for one of the absent parties would transfer their vote to the next best thing — and would not likely vote for the party targeted for defeat.

Results of the 2011 Canadian Election Study, conducted before and after that year’s federal election, show that the public’s political views are a little more complicated than that.

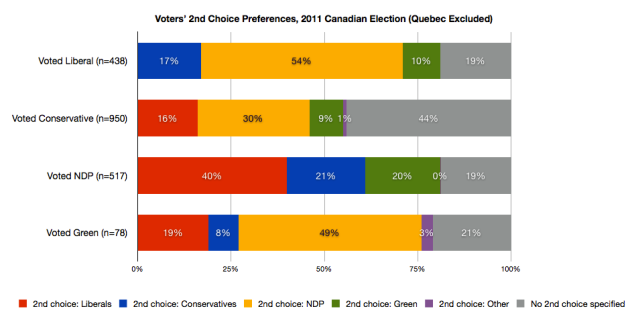

The graph below — based on voters from all parts of Canada except Quebec, to filter out the complicating role of the Bloc Quebecois — combines the results of two questions from that study: how respondents voted, and which party would have been their second choice. Among each of the three parties suggested as members of an anybody-but-the-Conservatives alliance — namely the Liberals, New Democrats and Greens — one-third or more would not have backed a fellow alliance member as a second choice. This includes about one-in-five in each case that had no second preference and might have just as easily not voted if deprived of their first choice, and even some who named the Conservatives as their second choice. (This, of course, works both ways: note the 30 percent of Conservative voters who said the NDP, nominally at the opposite end of the ideological spectrum, would have been their second choice.)

Canadians’ second-choice options in the 2011 federal election, by party actually voted for. (Source: Canadian Election Study, 2011. Quebec excluded; data not weighted.)

In the absence of a change to proportional representation whereby a party with 15 percent of the vote would win about 15 percent of the seats — a more radical change to Canada’s electoral systems, but not necessarily a bad one if combined with fixed election dates — those with an interest in inter-party cooperation might take note of Australia’s preferential ballot.

Used for elections to the lower house of the Australian Parliament, this ballot requires voters to rank candidates in order from most to least preferred. If a candidate wins more than 50 percent of the vote when the first preferences are tallied, he or she is declared elected. But if no one passes the 50 percent mark on the first count, the least successful candidates are progressively eliminated from the race and their votes are redistributed among the surviving candidates until someone tops 50 percent.

It must be cautioned that the Australian preferential ballot does not offer any great hope of a higher quality of representation or an improvement in citizen engagement. Australian politics can be just as inane as the Canadian version, and voter cynicism and alienation from the major parties is just as high there as it is here despite a compulsory voting law intended to encourage public involvement in politics.

It is also possible that a preferential ballot might not have even changed the outcome in Brandon-Souris.

Yet the change to such a ballot would give those who call for more inter-party cooperation against mutual foes a chance to put forward a constructive alternative to the current system — one that would not reduce voter choice, and which would leave the final outcome in the hands of voters themselves.

Recent Comments